5 Owls- Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Spoilers

Welcome to our spoiler-iffic Sorcerer’s Stone post!

This post is for readers who have finished the series and are using this opportunity to revisit Hogwarts. If you have not read ahead, please wait to read the rest of this post. Questions, polls, comments, etc. may expose you to important plot points, and if you’ve only read the first book, it’s too soon!!

In the comments we want to know:

- What did you notice in this book that comes back later? For example, Hagrid uses Sirius Black’s motorcycle on the day Harry was brought to the Dursley’s.

- Where does Prof. Quirrell rank among Defense Against the Dark Arts teachers?

- Could the characters have done anything differently in this book that would have affected the outcome of the series?

- Have your feelings about any of the characters we meet in Book 1 changed based on how they develop throughout the series?

Specifically:

Follow us on social media:

We ask library patrons under 13 to participate in these discussions with adult supervision. We would like to encourage families to incorporate discussion questions into their at-home book chats. This post is for discussing overarching theories and ideas, and for connecting what happens in this book to events in future installments. Spoil away.

Please be respectful.

Librarian’s Pick: On Swift Horses – Shannon Pufahl

“It’s 1956, and in the American West, military servicemen are returning from Korea and Japan looking for work, the fledgling interstate system is going up, and bomb tests draw Nevada tourists to watch the explosions. This is the backdrop for Shannon Pufahl’s assured debut, On Swift Horses, set in a time and place where the new and old rub up against each other, often uncomfortably.

“It’s 1956, and in the American West, military servicemen are returning from Korea and Japan looking for work, the fledgling interstate system is going up, and bomb tests draw Nevada tourists to watch the explosions. This is the backdrop for Shannon Pufahl’s assured debut, On Swift Horses, set in a time and place where the new and old rub up against each other, often uncomfortably.

As the novel opens, Muriel has left her native Kansas for Southern California to join her new husband, Lee. Lee gets a factory job, and Muriel waits tables at the Heyday Lounge near the Del Mar race track. As she listens to the bar’s regulars, she picks up some insider horse-racing knowledge, which she chooses not to share with Lee. She also pines for Julius, Lee’s unruly younger brother. Julius, meanwhile, gambles and risks his life, first in California, then in Las Vegas and Tijuana, Mexico.

As different as Muriel and Julius are, they both harbor secrets—one of which Muriel shares with Julius early in the story. And they’re both trying to find a way to love more truly and openly, since neither fits into the strictures that 1950s America wants to keep them in.

On Swift Horses offers many painful reminders of the damage that repression can do, but it’s also a deep-breathing, atmospheric novel. Pufahl renders postwar San Diego, the characters’ rural poverty and 1950s closeted gay life in careful detail, spinning plain language into beautiful images. Her prose carries hints of other writers who combine the bleak and the hopeful, such as Annie Proulx, Wallace Stegner and Kent Haruf. While the novel’s middle drags a little, Muriel’s and Julius’ journeys are compelling and surprising. Pufahl is a novelist to watch.”

Librarian’s Pick: Galway Girl -Ken Bruen

“Ken Bruen peppers his tales of world-weary ex-Garda (Irish cop) Jack Taylor with shamrock bromides that are often thought provoking or darkly humorous as Taylor muddles his violent way through the damp and peaty Irish landscape. “In Galway / They were forecasting a shortage of CO2 (no, me neither). / Which is what puts the kick, fizz, varoom in beer, soft drinks. / Ireland, without beer, in a heat wave.” You can almost hear the “tsk tsk” as Bruen imagines the mayhem that will ensue. Galway Girl finds Taylor beleaguered by a trio of spree killers targeting the Garda, a priest whose moral compass has been severely compromised and a surly falconer with an injured but nonetheless lethal bird of prey. Taylor’s ongoing battle with the demon rum (actually Jameson Irish Whiskey, in his case) hovers in the background of every scene, like some ominous uncle, familiar yet anything but benign. Bruen’s command of language and metaphor is on full display in his trademark staccato verse, and his sense of place is superb. And to top it all off, the final scene is so artfully and powerfully rendered that I had to go back and read it again. And again. And I likely will again.”

“Ken Bruen peppers his tales of world-weary ex-Garda (Irish cop) Jack Taylor with shamrock bromides that are often thought provoking or darkly humorous as Taylor muddles his violent way through the damp and peaty Irish landscape. “In Galway / They were forecasting a shortage of CO2 (no, me neither). / Which is what puts the kick, fizz, varoom in beer, soft drinks. / Ireland, without beer, in a heat wave.” You can almost hear the “tsk tsk” as Bruen imagines the mayhem that will ensue. Galway Girl finds Taylor beleaguered by a trio of spree killers targeting the Garda, a priest whose moral compass has been severely compromised and a surly falconer with an injured but nonetheless lethal bird of prey. Taylor’s ongoing battle with the demon rum (actually Jameson Irish Whiskey, in his case) hovers in the background of every scene, like some ominous uncle, familiar yet anything but benign. Bruen’s command of language and metaphor is on full display in his trademark staccato verse, and his sense of place is superb. And to top it all off, the final scene is so artfully and powerfully rendered that I had to go back and read it again. And again. And I likely will again.”

Librarian’s Pick: For Small Creatures Such as We – Sasha Sagan

“My parents taught me that the universe is enormous and we humans are tiny beings who get to live on an out-of-the-way planet for the blink of an eye,” writes author Sasha Sagan in the introduction of For Small Creatures Such as We, a gorgeous collection of essays that reads like a memoir.

“My parents taught me that the universe is enormous and we humans are tiny beings who get to live on an out-of-the-way planet for the blink of an eye,” writes author Sasha Sagan in the introduction of For Small Creatures Such as We, a gorgeous collection of essays that reads like a memoir.

The daughter of two of the 20th century’s most important contributors—astronomer Carl Sagan and producer Ann Druyan—Sagan began thinking deeply about the traditions and passages that shape life on earth after becoming a mother herself. Birth, anniversaries, fasting, atonement: She approaches these subjects with wonderment and a generous window into her extraordinary family history. A secular Jew who was raised by her famous parents to be an independent and deep thinker, Sagan demonstrates that rituals aren’t reserved purely for the religious.

“There is so much change in this world,” she writes. “So many entrances and exits and ways to mark them, each one astonishing in its own way. Even if we don’t see birth or life as a miracle in the theological sense, it’s still breathtakingly worthy of celebration.”

Sagan writes with stunning clarity and absolute joy. In the chapter on coming of age, Sagan connects puberty with the myth of the werewolf, before galloping through the rites of passage observed by the Amish, Mormons, Apaches, Japanese and her own family. When Sagan got her first period at age 13, her mother “took me in her arms and made me feel this was cause for celebration.” Contrast this with her mother’s experience as a Jew: Druyan’s mother slapped her across the face, as was the inexplicable custom in that time.

For Small Creatures Such as We is a marvel. It dazzles and comforts while making us consider our own place in the vast universe. As Sagan writes, “We are, after all, someone’s distant future and someone else’s ancient past.”

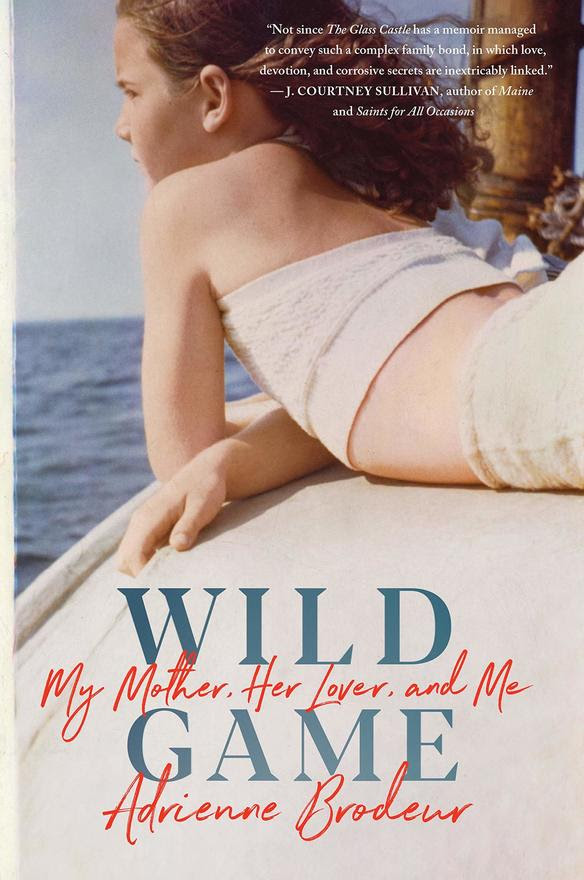

Librarian’s Pick: Wild Game:

“Wild Game: My Mother, Her Lover, and Me by Adrienne Brodeur is a story of one daughter’s moral contortions to make her mother, Malabar, happy. Brodeur learned the full contours of her mother’s discontent by becoming embroiled in her extramarital affair.

“Wild Game: My Mother, Her Lover, and Me by Adrienne Brodeur is a story of one daughter’s moral contortions to make her mother, Malabar, happy. Brodeur learned the full contours of her mother’s discontent by becoming embroiled in her extramarital affair.

Brodeur was only 14 when Malabar—a charming cookbook author wed to a wealthy man who soon fell ill after their marriage—divulged that she had taken a family friend, also married, as her lover. Brodeur kept their affair a secret from her stepfather, both families, her friends and, later, even her own spouse. Wild Game explores this secret’s impact on all of their lives, but primarily Brodeur’s own.

Brodeur knew her mother had suffered a tragic life due to parental abuse and the later death of a child. As Brodeur became personally invested in protecting the affair, she reveals herself to be an extraordinary case of the parentified child. Anyone with similar childhood circumstances will relate to the weightiness of filial duty depicted in Wild Game.

But Brodeur is also extraordinary for how, on the other side of this story, she has ended up basically OK. She’s married again, a parent herself and a lovely writer. (She is the former editor of Zoetrope: All-Story, a literary magazine she launched with Francis Ford Coppola.) Her talent with words lies in her ability to make the reader feel deeply empathetic for Malabar, while at the same time abhorring her behavior as a parent. Mother and daughter are, certainly, a perpetrator and a victim. But the reader is liable to be convinced, as Broedur is, that her mother was very much a victim, too.”

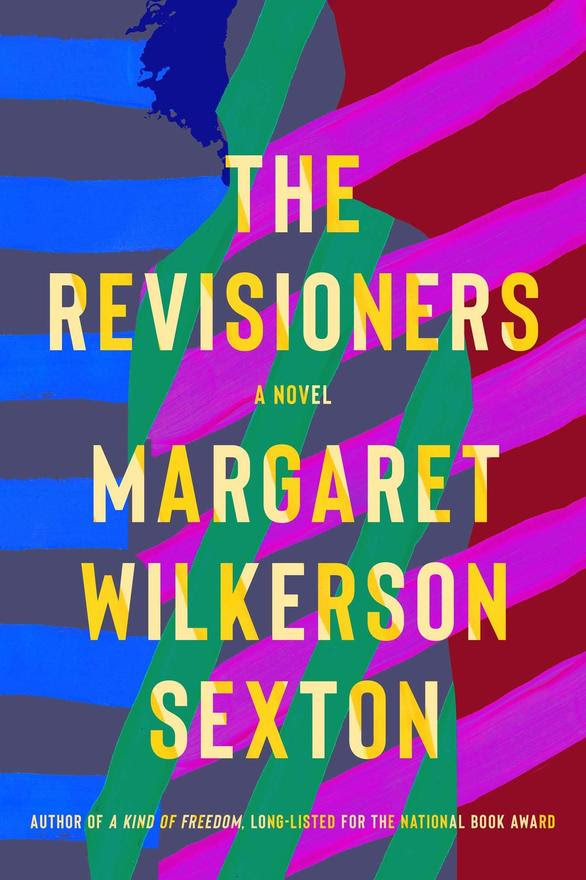

Librarian’s Pick: The Revisioners – Margaret Wilkerson Sexton

“In the 1920s, Josephine takes over her husband’s land after his death. The farm is flourishing, but when a suspicious white family moves in nearby, Josephine discovers too late their affiliation to the Ku Klux Klan. In 2017, Ava, a biracial single mother descended from Josephine, has just been laid off. She takes up her white grandmother’s offer to move in together, a proposal that seems attractive at first, until her grandmother begins to have violent outbursts.

“In the 1920s, Josephine takes over her husband’s land after his death. The farm is flourishing, but when a suspicious white family moves in nearby, Josephine discovers too late their affiliation to the Ku Klux Klan. In 2017, Ava, a biracial single mother descended from Josephine, has just been laid off. She takes up her white grandmother’s offer to move in together, a proposal that seems attractive at first, until her grandmother begins to have violent outbursts.

Sexton’s characters’ realistic interior thoughts drive the novel, revealing hidden emotions of apprehension and nostalgia. Ava and Josephine display an unusual ability to discern people’s motives; Ava has a unique perception of her mother, and Josephine understands her son’s struggle to break out from his father’s shadow. Though they experience the world at different times and through different circumstances, their worlds intersect through a shared purpose: to offer support, comfort and healing.

Despite everything, Ava and Josephine hold on to hope, refusing to be bound by the constraints of their eras. The Revisioners is an uplifting novel of black women and their tenacity.”